-

Australia's Head backs struggling opening partner Weatherald

Australia's Head backs struggling opening partner Weatherald

-

'Make emitters responsible': Thailand's clean air activists

-

Zelensky looks to close out Ukraine peace deal at Trump meet

Zelensky looks to close out Ukraine peace deal at Trump meet

-

MCG curator in 'state of shock' after Ashes Test carnage

-

Texans edge Chargers to reach NFL playoffs

Texans edge Chargers to reach NFL playoffs

-

Osimhen and Mane score as Nigeria win to qualify, Senegal draw

-

Osimhen stars as Nigeria survive Tunisia rally to reach second round

Osimhen stars as Nigeria survive Tunisia rally to reach second round

-

How Myanmar's junta-run vote works, and why it might not

-

Watkins wants to sicken Arsenal-supporting family

Watkins wants to sicken Arsenal-supporting family

-

Arsenal hold off surging Man City, Villa as Wirtz ends drought

-

Late penalty miss denies Uganda AFCON win against Tanzania

Late penalty miss denies Uganda AFCON win against Tanzania

-

Watkins stretches Villa's winning streak at Chelsea

-

Zelensky stops in Canada en route to US as Russia pummels Ukraine

Zelensky stops in Canada en route to US as Russia pummels Ukraine

-

Arteta salutes injury-hit Arsenal's survival spirit

-

Wirtz scores first Liverpool goal as Anfield remembers Jota

Wirtz scores first Liverpool goal as Anfield remembers Jota

-

Mane rescues AFCON draw for Senegal against DR Congo

-

Arsenal hold off surging Man City, Wirtz breaks Liverpool duck

Arsenal hold off surging Man City, Wirtz breaks Liverpool duck

-

Arsenal ignore injury woes to retain top spot with win over Brighton

-

Sealed with a kiss: Guardiola revels in Cherki starring role

Sealed with a kiss: Guardiola revels in Cherki starring role

-

UK launches paid military gap-year scheme amid recruitment struggles

-

Jota's children join tributes as Liverpool, Wolves pay respects

Jota's children join tributes as Liverpool, Wolves pay respects

-

'Tired' Inoue beats Picasso by unanimous decision to end gruelling year

-

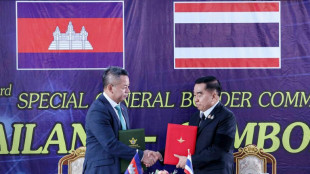

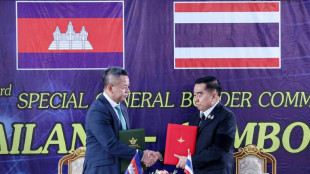

Thailand and Cambodia declare truce after weeks of clashes

Thailand and Cambodia declare truce after weeks of clashes

-

Netanyahu to meet Trump in US on Monday

-

US strikes targeted IS militants, Lakurawa jihadists, Nigeria says

US strikes targeted IS militants, Lakurawa jihadists, Nigeria says

-

Cherki stars in Man City win at Forest

-

Schwarz records maiden super-G success, Odermatt fourth

Schwarz records maiden super-G success, Odermatt fourth

-

Russia pummels Kyiv ahead of Zelensky's US visit

-

Smith laments lack of runs after first Ashes home Test loss for 15 years

Smith laments lack of runs after first Ashes home Test loss for 15 years

-

Russian barrage on Kyiv kills one, leaves hundreds of thousands without power

-

Stokes, Smith agree two-day Tests not a good look after MCG carnage

Stokes, Smith agree two-day Tests not a good look after MCG carnage

-

Stokes hails under-fire England's courage in 'really special' Test win

-

What they said as England win 4th Ashes Test - reaction

What they said as England win 4th Ashes Test - reaction

-

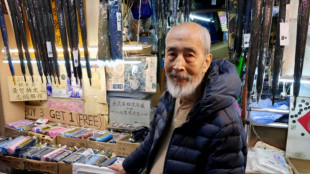

Hong Kongers bid farewell to 'king of umbrellas'

-

England snap 15-year losing streak to win chaotic 4th Ashes Test

England snap 15-year losing streak to win chaotic 4th Ashes Test

-

Thailand and Cambodia agree to 'immediate' ceasefire

-

Closing 10-0 run lifts Bulls over 76ers while Pistons fall

Closing 10-0 run lifts Bulls over 76ers while Pistons fall

-

England 77-2 at tea, need 98 more to win chaotic 4th Ashes Test

-

Somalia, African nations denounce Israeli recognition of Somaliland

Somalia, African nations denounce Israeli recognition of Somaliland

-

England need 175 to win chaotic 4th Ashes Test

-

Cricket Australia boss says short Tests 'bad for business' after MCG carnage

Cricket Australia boss says short Tests 'bad for business' after MCG carnage

-

Russia lashes out at Zelensky ahead of new Trump talks on Ukraine plan

-

Six Australia wickets fall as England fight back in 4th Ashes Test

Six Australia wickets fall as England fight back in 4th Ashes Test

-

New to The Street Show #710 Airs Tonight at 6:30 PM EST on Bloomberg Television

-

Dental Implant Financing and Insurance Options in Georgetown, TX

Dental Implant Financing and Insurance Options in Georgetown, TX

-

Man Utd made to 'suffer' for Newcastle win, says Amorim

-

Morocco made to wait for Cup of Nations knockout place after Egypt advance

Morocco made to wait for Cup of Nations knockout place after Egypt advance

-

Key NFL week has playoff spots, byes and seeds at stake

-

Morocco forced to wait for AFCON knockout place after Mali draw

Morocco forced to wait for AFCON knockout place after Mali draw

-

Dorgu delivers winner for depleted Man Utd against Newcastle

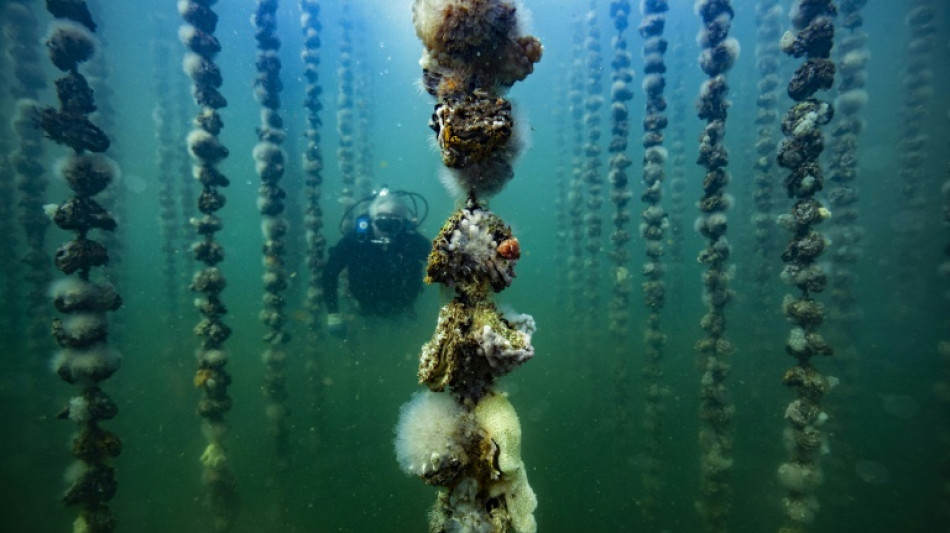

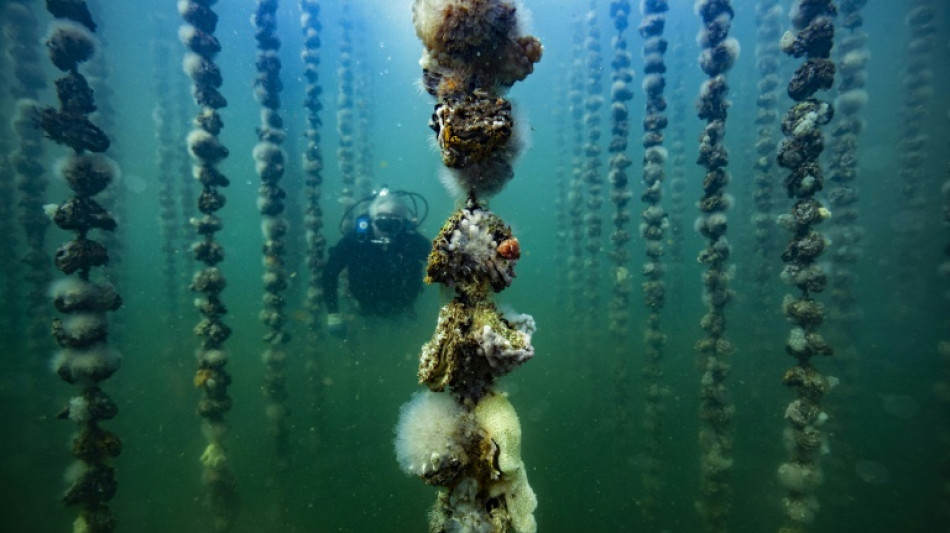

Drugs from the deep: scientists explore ocean frontiers

Some send divers in speed boats, others dispatch submersible robots to search the seafloor, and one team deploys a "mud missile" -- all tools used by scientists to scour the world's oceans for the next potent cancer treatment or antibiotic.

A medicinal molecule could be found in microbes scooped up in sediment, be produced by porous sponges or sea squirts -- barrel-bodied creatures that cling to rocks or the undersides of boats -- or by bacteria living symbiotically in a snail.

But once a compound reveals potential for the treatment of, say, Alzheimer's or epilepsy, developing it into a drug typically takes a decade or more, and costs hundreds of millions of dollars.

"Suppose you want to cure cancer -- how do you know what to study?" said William Fenical, a professor at Scripps Institution of Oceanography, considered a pioneer in the hunt for marine-derived medicines.

"You don't."

With tight budgets and little support from big pharma, scientists often piggyback on other research expeditions.

Marcel Jaspars of Scotland's University of Aberdeen said colleagues collect samples by dropping a large metal tube on a 5,000 metres (16,400 feet) cable that "rams" the seafloor. A more sophisticated method uses small, remotely operated underwater vehicles.

"I say to people, all I really want is a tube of mud," he told AFP.

This small but innovative area of marine exploration is in the spotlight at crucial UN high seas treaty negotiations, covering waters beyond national jurisdiction, which could wrap up this week with new rules governing marine protected areas crucial for protecting biodiversity.

Nations have long tussled over how to share benefits from marine genetic resources in the open ocean -- including compounds used in medicines, bioplastics and food stabilisers, said Daniel Kachelriess, a High Seas Alliance co-lead on the issue at the negotiations.

And yet only a small number of products with marine genetic resources find their way onto the market, with just seven recorded in 2019, he said. The value of potential royalties has been estimated at $10 million to $30 million a year.

But the huge biological diversity of the oceans means there is likely much more to be discovered.

"The more we look, the more we find," said Jaspars, whose lab specialises in compounds from the world's extreme environments, like underwater hydrothermal vents and polar regions.

- Natural origins -

Since Alexander Fleming discovered a bacteria-repelling mould he called penicillin in 1928, researchers have studied and synthesised chemical compounds made by mostly land-based plants, animals, insects and microbes to treat human disease.

"The vast majority of the antibiotics and anti-cancer drugs come from natural sources," Fenical told AFP, adding that when he started out in 1973, people were sceptical that the oceans had something to offer.

In one early breakthrough in the mid-1980s, Fenical and colleagues discovered a type of sea whip -- a soft coral -- growing on reefs in the Bahamas that produced a molecule with anti-inflammatory properties.

It caught the eye of cosmetics firm Estee Lauder, which helped develop it for use in its product at the time.

But the quantities of sea whips needed to research and market the compound ultimately led Fenical to abandon marine animals and instead focus on microorganisms.

Researchers scoop sediment from the ocean floor and then grow the microbes they find in the lab.

In 1991 Fenical and his colleagues found a previously-unknown marine bacterium called Salinispora in the mud off the coast of the Bahamas.

More than a decade of work yielded two anti-cancer drugs, one for lung cancer and the other for the untreatable brain tumour glioblastoma. Both are in the final stages of clinical trials.

Fenical -- who at 81 still runs a lab at Scripps -- said researchers were thrilled to have got this far, but the excitement is tempered by caution.

"You never know if something is going to be really good, or not at all useful," he said.

- New frontiers -

That long pipeline is no surprise to Carmen Cuevas Marchante, head of research and development at the Spanish biotech firm PharmaMar.

For their first drug, they started out by cultivating and collecting some 300 tonnes of the bulbous sea squirt.

"From one tonne we could isolate less than one gram" of the compound they needed for clinical trials, she told AFP.

The company now has three cancer drugs approved, all derived from sea squirts, and has fine-tuned its methods for making synthetic versions of natural compounds.

Even if everything goes right, Marchante said, it can take 15 years between discovery and having a product to market.

Overall, there have been 17 marine-derived drugs approved to treat human disease since 1969, with some 40 in various stages of clinical trials around the world, according to the online tracker Marine Drug Pipeline.

Those already on the market include a herpes antiviral from a sponge and a powerful pain drug from a cone snail, but most treat cancer.

That, experts say, is partly because the huge costs of clinical trials -- potentially topping a billion dollars -- favours the development of more expensive drugs.

But there is a "myriad" of early-stage research on marine-derived compounds for anything from malaria to tuberculosis, said Alejandro Mayer, a pharmacology professor at Illinois' Midwestern University who runs the Marine Pipeline project and whose own speciality is the brain's immune system.

That means there is still huge potential to find the next antibiotic or HIV therapy, scientists say.

It might be produced by a creature buried in ocean sediment or quietly clinging to a boat's hull.

Or it could be already in our possession: laboratories around the world hold libraries of compounds that can be tested against new diseases.

"There's a whole new frontier out there," said Fenical.

M.Fischer--AMWN