-

Trump imposes 10% global tariff after stinging court rebuke

Trump imposes 10% global tariff after stinging court rebuke

-

Floyd Mayweather to come out of retirement

-

Xbox boss Phil Spencer retires as Microsoft shakes up gaming unit

Xbox boss Phil Spencer retires as Microsoft shakes up gaming unit

-

158 giant tortoises reintroduced to a Galapagos island

-

What's next after US Supreme Court tariff ruling?

What's next after US Supreme Court tariff ruling?

-

Canada and USA to meet in ice hockey gold medal showdown at Winter Olympics

-

Jake Paul requires second jaw surgery after Joshua knockout

Jake Paul requires second jaw surgery after Joshua knockout

-

'Boldly headbang': Star Trek's Shatner, 94, unveils metal album

-

Marseille lose first Ligue 1 game of Beye era

Marseille lose first Ligue 1 game of Beye era

-

Police battle opposition protesters in Albanian capital

-

Austria snowstorm leaves five dead, road and power chaos

Austria snowstorm leaves five dead, road and power chaos

-

Trump unleashes personal assault on 'disloyal' Supreme Court justices

-

'Not the end': Small US firms wary but hopeful on tariff upheaval

'Not the end': Small US firms wary but hopeful on tariff upheaval

-

US freestyle skier Ferreira wins Olympic halfpipe gold

-

Svitolina edges Gauff to set up Pegula final in Dubai

Svitolina edges Gauff to set up Pegula final in Dubai

-

'Proud' Alcaraz digs deep to topple Rublev and reach Qatar final

-

UK govt considers removing ex-prince Andrew from line of succession

UK govt considers removing ex-prince Andrew from line of succession

-

New study probes why chronic pain lasts longer in women

-

Trump vows 10% global tariff after stinging court rebuke

Trump vows 10% global tariff after stinging court rebuke

-

Aston Martin in disarray as Leclerc tops F1 testing timesheets

-

Venus Williams accepts Indian Wells wild card

Venus Williams accepts Indian Wells wild card

-

Anxious Venezuelans seek clarity on new amnesty law

-

Last-gasp Canada edge Finland to reach Olympic men's ice hockey final

Last-gasp Canada edge Finland to reach Olympic men's ice hockey final

-

Scotland captain Tuipulotu grateful for Wales boss Tandy's influence

-

Zelensky says no 'family day' in rare personal interview to AFP

Zelensky says no 'family day' in rare personal interview to AFP

-

Zelensky tells AFP that Ukraine is not losing the war

-

Sweden to play Switzerland in Olympic women's curling final

Sweden to play Switzerland in Olympic women's curling final

-

Counting the cost: Minnesota reels after anti-migrant 'occupation'

-

UK police probe Andrew's protection as royals reel from ex-prince's arrest

UK police probe Andrew's protection as royals reel from ex-prince's arrest

-

Doris says Ireland must pile pressure on England rising star Pollock

-

US military assets in the Middle East

US military assets in the Middle East

-

Neymar hints at possible retirement after World Cup

-

Stocks rise after court ruling against US tariffs

Stocks rise after court ruling against US tariffs

-

Australia end dismal T20 World Cup by thrashing Oman

-

Olympics chief says Milan-Cortina has set new path for Games

Olympics chief says Milan-Cortina has set new path for Games

-

Russian SVR spy agency took over Wagner 'influence' ops in Africa: report

-

Pegula fights back to sink Anisimova and reach Dubai final

Pegula fights back to sink Anisimova and reach Dubai final

-

Trump administration denounces 'terrorism' in France after activist's killing

-

Colombia's Medellin builds mega-prison inspired by El Salvador's CECOT

Colombia's Medellin builds mega-prison inspired by El Salvador's CECOT

-

German broadcaster recalls correspondent over AI-generated images

-

US Supreme Court strikes down swath of Trump global tariffs

US Supreme Court strikes down swath of Trump global tariffs

-

England's Itoje says managing 'emotional turmoil' key to 100 cap landmark

-

Trump says weighing strike on Iran as Tehran says draft deal coming soon

Trump says weighing strike on Iran as Tehran says draft deal coming soon

-

Tudor is '100 percent' certain of saving Spurs from relegation

-

Azam dropped for scoring too slowly, says Pakistan coach Hesson

Azam dropped for scoring too slowly, says Pakistan coach Hesson

-

Stocks volatile after soft US growth data, court ruling against tariffs

-

Italy bring back Capuozzo for France Six Nations trip

Italy bring back Capuozzo for France Six Nations trip

-

From Malinin's collapse to Liu's triumph: Top Olympic figure skating moments

-

Arteta urges Arsenal to 'write own destiny' after title wobble

Arteta urges Arsenal to 'write own destiny' after title wobble

-

Ukraine Paralympics team to boycott opening ceremony over Russian flag decision

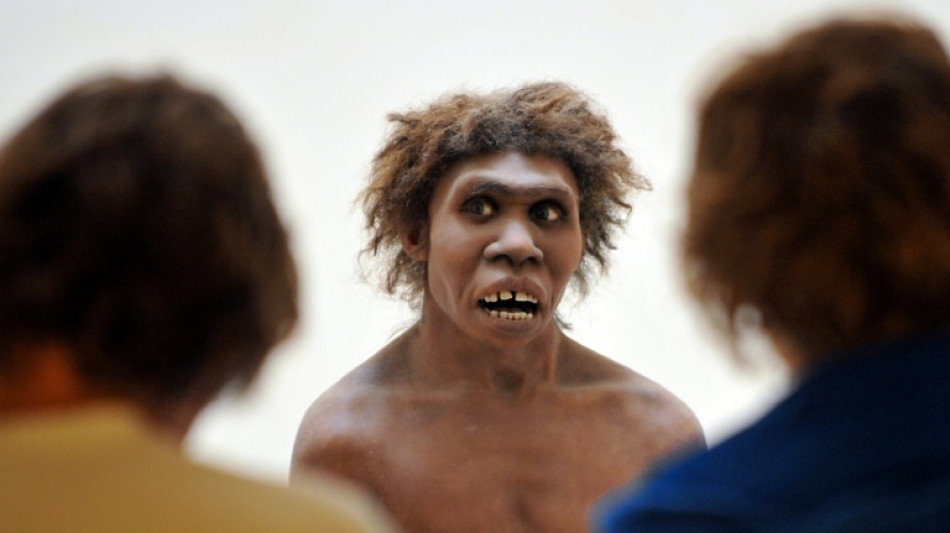

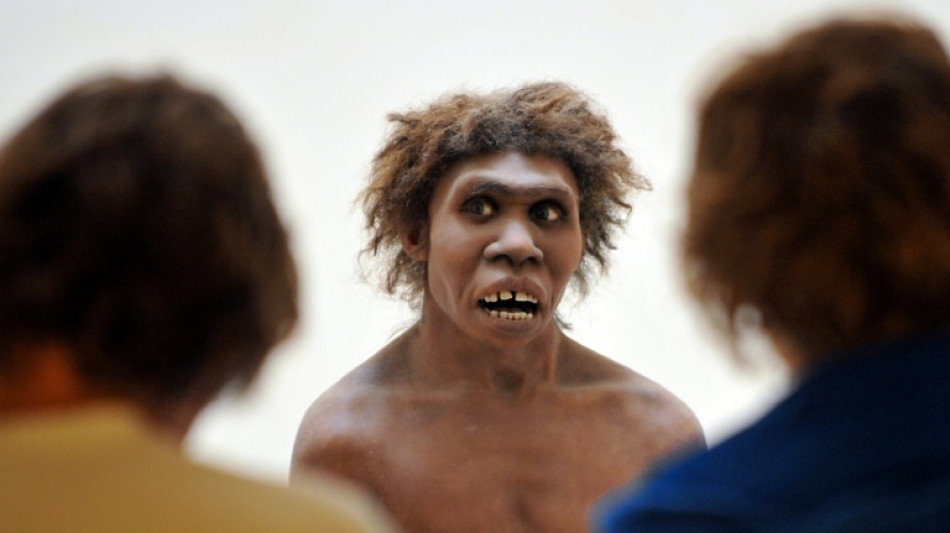

Homo erectus, not sapiens, first humans to survive desert: study

Our ancestor Homo erectus was able to survive punishingly hot and dry desert more than a million years ago, according to a new study that casts doubt on the idea that Homo sapiens were the first humans capable of living in such hostile terrain.

The moment when the first members of the extended human family called hominins adapted to life in desert or tropical forests marks "a turning point in the history of human survival and expansion in extreme environments," lead study author Julio Mercader Florin of the University of Calgary told AFP.

Scientists have long thought that only Homo sapiens, who first appeared around 300,000 years ago, were capable of living sustainably in such inhospitable regions.

The first hominins to have split off from the other great apes were believed to be limited to less hostile ecosystems, such as forest, grasslands and wetlands.

One of the world's most important prehistoric sites, Olduvai Gorge in modern-day Tanzania, was thought to home to those easier types of landscapes.

But this steep ravine in East Africa's Great Rift Valley, which has played a key role in the understanding of human evolution, was actually a desert steppe, according to the study published in the journal Communications Earth & Environment on Thursday.

After collecting archaeological, geological and palaeoclimatic data, the international team of researchers were able to reconstruct the gorge's ecosystem over the years.

Fossilised pollen of the Ephedra shrub -- which commonly lives in arid areas -- as well as traces of past wildfires and signs in the soil show there was an extreme drought in the area between one and 1.2 million years ago.

- Homo erectus: underestimated? -

Evidence collected from the Engaji Nanyori site in the gorge suggests that Homo erectus adapted to this hostile environment "by focusing on ecological focal points such as river confluences where water and food resources were more predictable", Mercader Florin said.

"Their ability to repeatedly exploit these focal points... and adapt their behaviours to extreme environments demonstrates a higher level of resilience and strategic planning than previously assumed."

Specialised tools found at the site, such as hand axes, scrapers and cleavers, showed that Homo erectus had also worked out how to process animal carcasses.

The bones of animals such as cows, hippopotamuses, crocodiles and antelopes also had cut marks, indicating they had been skinned and had their bone marrow extracted.

"This suggests they optimised their resource use to adapt to the challenges of arid environments, where resources were scarce and needed to be exploited fully," Mercader Florin said.

"Our findings show that Homo erectus was capable of surviving long term in extreme environments characterised by low density of food resources, navigational challenges, very low/very high plant life, temperature/humidity extremes, and the need for high mobility," he added.

"This adaptability expands Homo erectus's potential range into the Saharo-Sindian region across Africa and into similar environments in Asia."

O.Johnson--AMWN