-

Zelensky looks to close out Ukraine peace deal at Trump meet

Zelensky looks to close out Ukraine peace deal at Trump meet

-

MCG curator in 'state of shock' after Ashes Test carnage

-

Texans edge Chargers to reach NFL playoffs

Texans edge Chargers to reach NFL playoffs

-

Osimhen and Mane score as Nigeria win to qualify, Senegal draw

-

Osimhen stars as Nigeria survive Tunisia rally to reach second round

Osimhen stars as Nigeria survive Tunisia rally to reach second round

-

How Myanmar's junta-run vote works, and why it might not

-

Watkins wants to sicken Arsenal-supporting family

Watkins wants to sicken Arsenal-supporting family

-

Arsenal hold off surging Man City, Villa as Wirtz ends drought

-

Late penalty miss denies Uganda AFCON win against Tanzania

Late penalty miss denies Uganda AFCON win against Tanzania

-

Watkins stretches Villa's winning streak at Chelsea

-

Zelensky stops in Canada en route to US as Russia pummels Ukraine

Zelensky stops in Canada en route to US as Russia pummels Ukraine

-

Arteta salutes injury-hit Arsenal's survival spirit

-

Wirtz scores first Liverpool goal as Anfield remembers Jota

Wirtz scores first Liverpool goal as Anfield remembers Jota

-

Mane rescues AFCON draw for Senegal against DR Congo

-

Arsenal hold off surging Man City, Wirtz breaks Liverpool duck

Arsenal hold off surging Man City, Wirtz breaks Liverpool duck

-

Arsenal ignore injury woes to retain top spot with win over Brighton

-

Sealed with a kiss: Guardiola revels in Cherki starring role

Sealed with a kiss: Guardiola revels in Cherki starring role

-

UK launches paid military gap-year scheme amid recruitment struggles

-

Jota's children join tributes as Liverpool, Wolves pay respects

Jota's children join tributes as Liverpool, Wolves pay respects

-

'Tired' Inoue beats Picasso by unanimous decision to end gruelling year

-

Thailand and Cambodia declare truce after weeks of clashes

Thailand and Cambodia declare truce after weeks of clashes

-

Netanyahu to meet Trump in US on Monday

-

US strikes targeted IS militants, Lakurawa jihadists, Nigeria says

US strikes targeted IS militants, Lakurawa jihadists, Nigeria says

-

Cherki stars in Man City win at Forest

-

Schwarz records maiden super-G success, Odermatt fourth

Schwarz records maiden super-G success, Odermatt fourth

-

Russia pummels Kyiv ahead of Zelensky's US visit

-

Smith laments lack of runs after first Ashes home Test loss for 15 years

Smith laments lack of runs after first Ashes home Test loss for 15 years

-

Russian barrage on Kyiv kills one, leaves hundreds of thousands without power

-

Stokes, Smith agree two-day Tests not a good look after MCG carnage

Stokes, Smith agree two-day Tests not a good look after MCG carnage

-

Stokes hails under-fire England's courage in 'really special' Test win

-

What they said as England win 4th Ashes Test - reaction

What they said as England win 4th Ashes Test - reaction

-

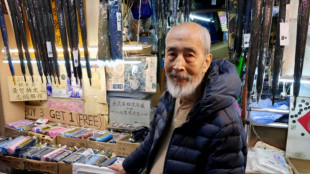

Hong Kongers bid farewell to 'king of umbrellas'

-

England snap 15-year losing streak to win chaotic 4th Ashes Test

England snap 15-year losing streak to win chaotic 4th Ashes Test

-

Thailand and Cambodia agree to 'immediate' ceasefire

-

Closing 10-0 run lifts Bulls over 76ers while Pistons fall

Closing 10-0 run lifts Bulls over 76ers while Pistons fall

-

England 77-2 at tea, need 98 more to win chaotic 4th Ashes Test

-

Somalia, African nations denounce Israeli recognition of Somaliland

Somalia, African nations denounce Israeli recognition of Somaliland

-

England need 175 to win chaotic 4th Ashes Test

-

Cricket Australia boss says short Tests 'bad for business' after MCG carnage

Cricket Australia boss says short Tests 'bad for business' after MCG carnage

-

Russia lashes out at Zelensky ahead of new Trump talks on Ukraine plan

-

Six Australia wickets fall as England fight back in 4th Ashes Test

Six Australia wickets fall as England fight back in 4th Ashes Test

-

New to The Street Show #710 Airs Tonight at 6:30 PM EST on Bloomberg Television

-

Dental Implant Financing and Insurance Options in Georgetown, TX

Dental Implant Financing and Insurance Options in Georgetown, TX

-

Man Utd made to 'suffer' for Newcastle win, says Amorim

-

Morocco made to wait for Cup of Nations knockout place after Egypt advance

Morocco made to wait for Cup of Nations knockout place after Egypt advance

-

Key NFL week has playoff spots, byes and seeds at stake

-

Morocco forced to wait for AFCON knockout place after Mali draw

Morocco forced to wait for AFCON knockout place after Mali draw

-

Dorgu delivers winner for depleted Man Utd against Newcastle

-

US stocks edge lower from records as precious metals surge

US stocks edge lower from records as precious metals surge

-

Somalia denounces Israeli recognition of Somaliland

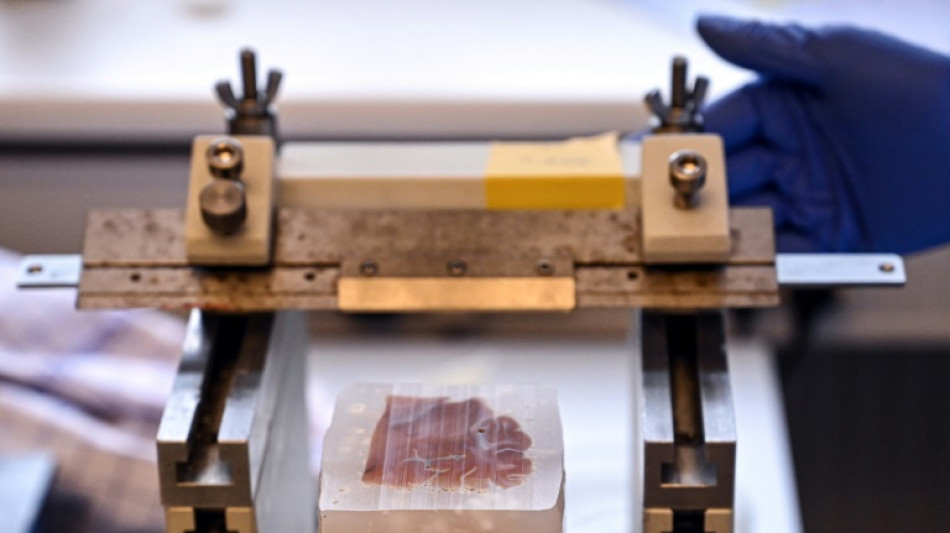

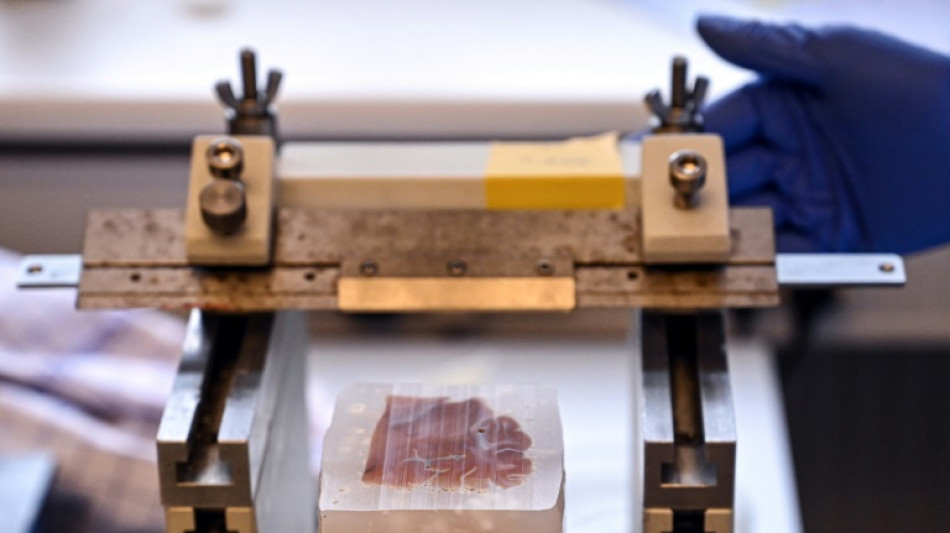

Grey area: chilling past of world's biggest brain collection

Countless shelves line the walls of a basement at Denmark's University of Odense, holding what is thought to be the world's largest collection of brains.

There are 9,479 of the organs, all removed from the corpses of mental health patients over the course of four decades until the 1980s.

Preserved in formalin in large white buckets labelled with numbers, the collection was the life's work of prominent Danish psychiatrist Erik Stromgren.

Begun in 1945, it was a "kind of experimental research," Jesper Vaczy Kragh, an expert in the history of psychiatry, explained to AFP.

Stromgren and his colleagues believed "maybe they could find out something about where mental illnesses were localised, or they thought they might find the answers in those brains".

The brains were collected after autopsies had been conducted on the bodies of people committed to psychiatric institutes across Denmark.

Neither the deceased nor their families were ever asked permission.

"These were state mental hospitals and there were no people from the outside who were asking questions about what went on in these state institutions," he said.

At the time, patients' rights were not a primary concern.

On the contrary, society believed it needed to be protected from these people, the researcher from the University of Copenhagen said.

Between 1929 and 1967, the law required people committed to mental institutions to be sterilised.

Up until 1989, they had to get a special exemption in order to be allowed to marry.

Denmark considered "mentally ill" people, as they were called at the time, "a burden to society (and believed that) if we let them have children, if we let them loose... they will cause all kinds of trouble," Vaczy Kragh said.

Back then, every Dane who died was autopsied, said pathologist Martin Wirenfeldt Nielsen, the director of the collection.

"It was just part of the culture back then, an autopsy was just another hospital procedure," Nielsen said.

The evolution of post-mortem procedures and growing awareness of patients' rights heralded the end of new additions to the collection in 1982.

A long and heated debate then ensued on what to do with it.

Denmark's state ethics council ultimately ruled it should be preserved and used for scientific research.

- Unlocking hidden secrets -

The collection, long housed in Aarhus in western Denmark, was moved to Odense in 2018.

Research on the collection has over the years covered a wide range of illnesses, including dementia, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and depression.

"The debate has basically settled down, and (now people) say 'okay, this is very impressive and useful scientific research if you want to know more about mental disease'," the collection's director said.

Some of the brains belonged to people who suffered from both mental health issues and brain illnesses.

"Because many of these patients were admitted for maybe half their life, or even their entire life, they would also have had other brain diseases, such as a stroke, epilepsy or brain tumours," he added.

Four research projects are currently using the collection.

"If it's not used, it does no good," says the former head of the country's mental health association, Knud Kristensen.

"Now we have it, we should actually use it," he said, complaining about a lack of resources to fund research.

Neurobiologist Susana Aznar, a Parkinson's expert working at a Copenhagen research hospital, is using the collection as part of her team's research project.

She said the brains were unique in that they enable scientists to see the effects of modern treatments.

"They were not treated with the treatments that we have now," she said.

The brains of patients nowadays may have been altered by the treatments they have received.

When Aznar's team compares these with the brains from the collection, "we can see whether these changes could be associated with the treatments," she said.

Y.Aukaiv--AMWN